Torn Pages

By: Sid

While at work today, I stumbled upon Torn write prevention on Amazon EC2 Linux instances and I dived deeper ^u^

What is a Torn Write?

A torn write occurs when a write operation to persistent storage like our disks is interrupted, resulting in only part of the intended data being written. This leaves the data in an inconsistent or corrupted state.

This isn't good cause disks promise atomicity at the sector level (which is usually 512 bytes) whereas, DB’s operate on larger pages (usually 4KB or 8KB)[alot of pages] so basically, if only some sectors of a page are written, the page will eventually end up becoming inconsistent and this is what is called a torn page

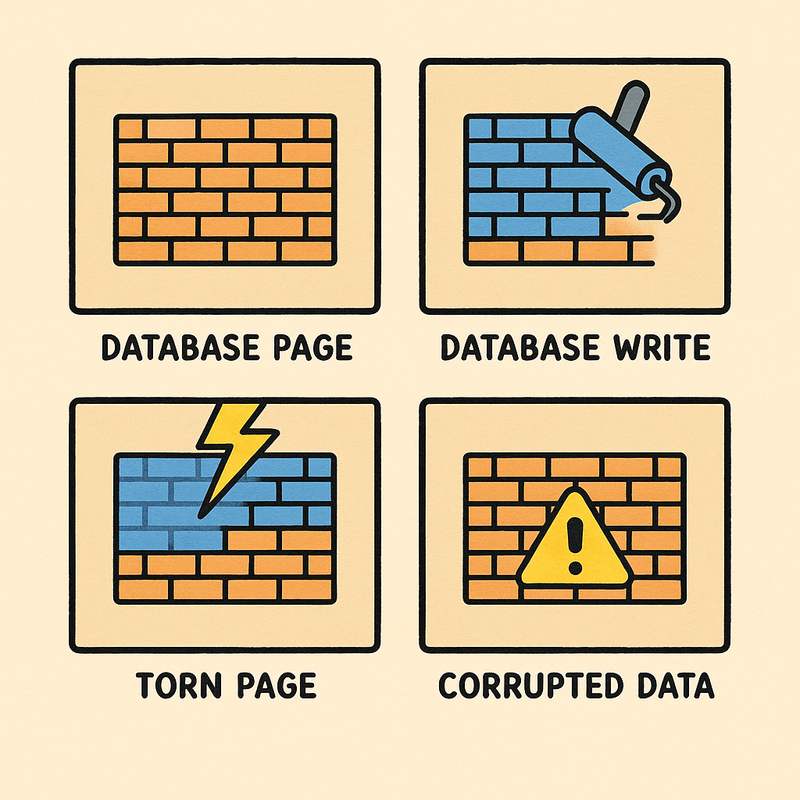

Heres an example that helped me visualize it :

> A database page is like a wall made of bricks (sectors).

> The database tries to write the whole wall (page) at once.

> A power failure during write leaves the wall half old, half new basically, a torn page!

> The page is now inconsistent and may be corrupted.

Why Do Torn Writes Happen?

It can be anything from a Power Loss where a sudden power failure interrupts in-progress writes to a Crash where system or hardware crashes can halt writes mid-operation.

Other factors could be the Write Granularity of the Disks, where they write in fixed-size blocks (e.g., 512B, 4KB). If your write spans multiple blocks, a crash can leave some blocks updated and others not :/

or the Lack of Atomicity

What's the impact ?

An incomplete write will lead to Corrupt Data, and can even put the disk in an unrecoverable state.

Databases could use complex recovery logic to detect and fix torn writes.

So, what did DB’s do to detect this ?

1. Detection Only (Sector Counters)

Each sector includes a counter that increments with every write and if a page is read and the counters don’t match, it’s a torn page.

This is a lightweight method and doesn’t require full checksums.

2. SQL Server’s Torn Page Detection

SQL Servers have a 8KB page size.

SQL provides a Torn Page detection where the SQL Server uses the first two bits of each 512-byte sector and then concatenate them into a 32-bit value and stored in the page header.

On write, the bits are replaced with a 2-bit counter and if the counters don’t match on read, the page is flagged as suspect.

Oracle on the other hand has a 8KB page size, and it's RDBMS can detect torn writes by comparing the System Change Number (SCN) stored in the page header with a copy of the SCN kept at the end (tail) of the page.

If a torn page is found, an administrator must perform media recovery using tools like DBMS_REPAIR or RMAN to repair the corrupted blocks. When the DB_BLOCK_CHECKSUM=TYPICAL , torn pages are detected as checksum errors.

However, even if checksumming is turned off, Oracle can still identify torn pages by checking for mismatches between the header and tail SCNs.

3. Log Full Pages

> Log the entire update page into the WAL(Write Ahead Log) before writing.(for each page that is updated)

> The same updated page is then written to the main database file (e.g., the B-Tree structure on disk).

> On recovery, use the log to restore the full page from the WAL to the B-Tree

Clearly, this isn't effective in case of storage space as each page is written on change instead of just the modified part and also each page is now written twice.

- SQLite defaults to a 4KB page size and follows this approach to torn page protection (which they call "powersafe overwrite").

During a checkpoint, performed at COMMIT or after 1000 pages are written, all pages are applied from the WAL back to the B-Tree. Checkpointing can thus only be done when there are no open transactions, and long-running write transactions can cause the WAL to grow significantly.

4. Log Page on First Write

> Only log the page the first time it’s written in a transaction and then in case of failure, the older version of the page can be fetched from the write-ahead log, and all the changes can be applied to produce the correct page contents.

> This does reduce the logging overhead compared to the full page approach

⚠️ As checkpointing removes previous write-ahead log files, pages will need to be copied to the write-ahead log on their first modification following each checkpoint.

The normal state will trend towards ~1x write amplification instead of the 2x from before

Postgres has an 8KB page size and utilizes this torn write protection technique, which it calls full page writes.

The page images are compressed before being stored in the write-ahead log.

During recovery, PostgreSQL always restores these full page images and then reapplies all logged changes to the pages.This approach helps avoid random I/O on the write-ahead log during recovery.

5. Double-Write Buffer

Intuition behind this : Why rely on the WAL when we can move the torn write protection entirely to the B-Tree?

> Write the page twice: once to a special buffer, then to its final location.

> When a B-Tree page is updated, the database first writes the entire updated page to the double-write buffer (or commonly known as the scratch space).

This buffer is separate from the main data files.

After the page is safely written to the double-write buffer, the database then writes the page to its final location in the main data file.

> The idea here is that the double-write buffer will always have a complete, correct copy of the page (because the buffer is written atomically, and the database checks that the write is completed successfully).

During recovery, the database can check the double-write buffer and, if it finds a torn page in the main file, it can restore the correct version from the buffer.

Also, when WAL gets bigger, commits can be slower, that won't happen here

Whats wrong ?

Clearly a 2x write and space amplification as we write to the scratch space and the main data file :/ [Just like the Full Page Logging but here, we dont rely on a WAL]

- MySQL’s InnoDB (and similar databases like XtraDB and CedarDB) uses a 16KB page size and is famous for using the double-write buffer method. They don’t have to wait for the WAL to finish writing full page images before it can commit a transaction.

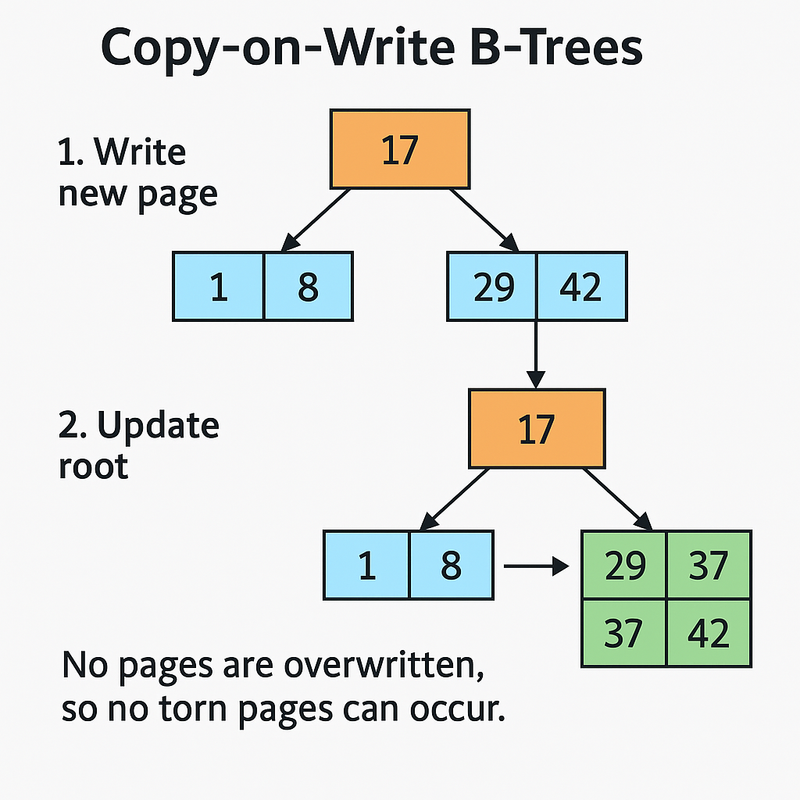

6. Copy on Write

This basically attacks the core reason behind how torn pages happen. Torn pages basically happen when you update pages in-place i.e. overwrite the same spot on disk, so if you fix this : problem solved xD

> When you want to update a page, don’t overwrite the old page.

> Create a new page with the updated data and write it to a new spot on disk and then just update metadata to point to the new version.

But updating the parent is also a change, so you copy the parent and update its pointer. This process repeats up to the root of the B-Tree.

No need for a write-ahead log : the tree itself is always consistent. ٩(^ᗜ^ )و

No need for a write-ahead log : the tree itself is always consistent. ٩(^ᗜ^ )و

Ensures atomicity but requires extra space and metadata management.

This is where I came across this cool Data Structure called the LSM (Log-Structured Merge) trees

These trees by design never update in place—they only append new data. That’s why LSMs are immune to torn pages by design.

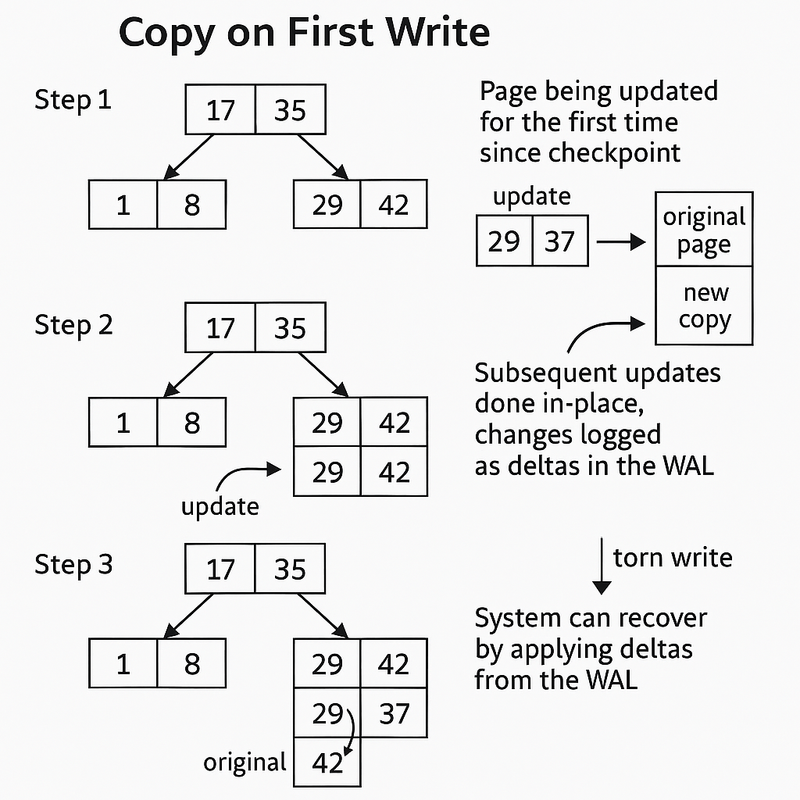

7. Copy on First Write

It’s a hybrid technique that combines the best parts of Copy-on-Write, Double-Write Buffer, and Write-Ahead Logging (WAL)

> When a page in the B-Tree is updated for the first time since the last checkpoint, make a copy of the original page (just like Copy-on-Write).The update is applied to the new copy, and the B-Tree is updated to point to this new page. The old version is kept around until the next checkpoint finishes.

but but but, here’s whats diff from copy on write :

If the same page is updated again before the next checkpoint, it’s updated in-place (no more copying !).

Each change will now be logged as a delta, not the full page.

This realllyyy balances performance and safety cause only the first update to a page in each checkpoint interval requires a copy (so, less write amplification than always copying) later updates are fast, in-place changes.

The issue is that we have to keep the old versions of pages around until the next checkpoint, which uses more disk space (space amplification).

OrioleDB [and some mordern search engines] is the only widely-known database that uses this exact “Copy on First Write” strategy as described.

8. Atomic Multi-Block Writes

- Linux 🐧[only penguin emoji I found :( ] is adding support for true atomic writes at the filesystem level.

- Atomic write means: the whole write either happens completely, or not at all—no torn pages!

So, they basically introduced a set of new system calls and flags :

pwritev2(): A system call for writing data to files.RWF_ATOMIC: A new flag you can pass topwritev2()to request atomic writes.

How do we utilize this ?

1.Open your file with O_DIRECT (bypasses the OS cache).

2.Make sure your writes are aligned and sized according to what statx() [statx can ask the filesystem and hardware what sizes of atomic writes is supported]

3.Use pwritev2() with the RWF_ATOMIC flag.

⚠️ If you try to write too much at once, or use too many segments, you’ll get an error.

How Does Multi-Block Atomicity Work?

For larger atomic writes, Linux will use a copy-on-write-like approach:

1.Write the new data to a new area (extent) on disk.

2.Update the file’s metadata to point to the new data.

This is safe, but means two fsync() operations (so, two disk flushes), and more metadata overhead.

What Does This Mean for Databases?

> Databases can now rely on the filesystem to prevent torn pages—no need to write full pages to the WAL or use double-write buffers, if the hardware and filesystem support it.

> AlloyDB Omni is an example: it can use RWF_ATOMIC and turn off full_page_writes, making writes faster and using less disk space.

Should You Still Worry About Torn Writes?

> If You Use Modern Storage and Filesystems: Torn writes are rare. Most modern systems guarantee atomic 4KB writes.

> Checksums and WAL are still best practice. They protect against other forms of corruption (e.g., bit rot, firmware bugs).

> Doublewrite buffers may be redundant. Some databases are removing them for performance.

Some argue that enterprise SSDs equipped with supercapacitors for power-loss protection, the same technology often cited for enabling asynchronous completion of fsync() are also resistant to torn writes.

How Amazon (AWS) Handles Torn Writes

If you’re running databases or applications on AWS, you’re likely using Amazon EBS (Elastic Block Store) for persistent storage. AWS has engineered EBS to minimize the risk of torn writes and data corruption.

EBS Atomicity Guarantees

> Atomic 512-byte sector writes: EBS guarantees that a single 512-byte sector write is atomic. After a successful write, the sector contains either the old data or the new data—never a mix.

> Replication: EBS volumes are automatically replicated within an Availability Zone, protecting against hardware failure and increasing durability.

> Consistency: EBS is designed to provide consistent and durable storage, even in the event of hardware failure.

Note: While EBS guarantees atomicity at the 512-byte sector level, larger writes (e.g., 4KB, 8KB) are only atomic if they are aligned and issued as a single write operation by the OS or application.